Recently, I had an eye-opening conversation with a self-proclaimed successful salesperson, Mr. B, who epitomized the luxury of our consumer-driven society. This was not our first encounter, but it was, by far, the most illuminating. Dressed in a tailored suit that likely cost more than my monthly mortgage, he exuded an air of success, punctuated by the glint of a diamond-studded watch that could have easily adorned a crown.

“Another round of the wagyu, please!” he bellowed to the waiter, his charisma as thick as the prime cut of beef he was about to devour—a delicacy the average person could only dream of savoring. As the waiter prepared his order, Mr. B leaned back with a satisfied smirk, eyes twinkling with the thrill of indulging in the best life could offer.

Yet, despite the opulence, a sense of unease began to settle in. Between bites of his extravagant meal, he lamented the rising cost of living as though it were an unbearable weight on his shoulders. “Can you believe how much fuel my sports car consumes? It’s absurd! And first-class flights? Don’t even get me started,” he exclaimed, shaking his head dramatically.

The dichotomy was stark. Here was a man enjoying the finer things in life—a wealthy embodiment of success—yet he spoke of struggling in a business environment that, by all appearances, had treated him well. It struck me as a performative act, a desperate grasp for empathy amidst indulgence. He then dropped the bombshell: “Business is slow right now, and I might need to reach my personal sales target at any costs.” He nonchalantly brought up the idea of promoting higher-margin products rather than truly addressing his clients’ needs, masking his words with an insincere smile. “Everyone has to eat, after all,” he said. And morality cannot be consumed indeed.

I felt a surge of disgust wash over me. This was the very picture of privilege, expressing woes that felt trivial compared to those of everyday families fighting to put food on their tables. Where was the empathy in that notion? I couldn’t help but glance around the upscale restaurant, noticing that, in a first-world country with affluence on display, Mr. B represented an unsettling reminder of how easily we normalize an escalating standard of living.

That unsettling thought lingered as he continued. “You know, affluent income classes, as they say, redefine what is considered a normal lifestyle. The moment you achieve a certain status, it’s like a race—you always need to reach higher, achieve more. They call it progress, but does it come at a cost?”

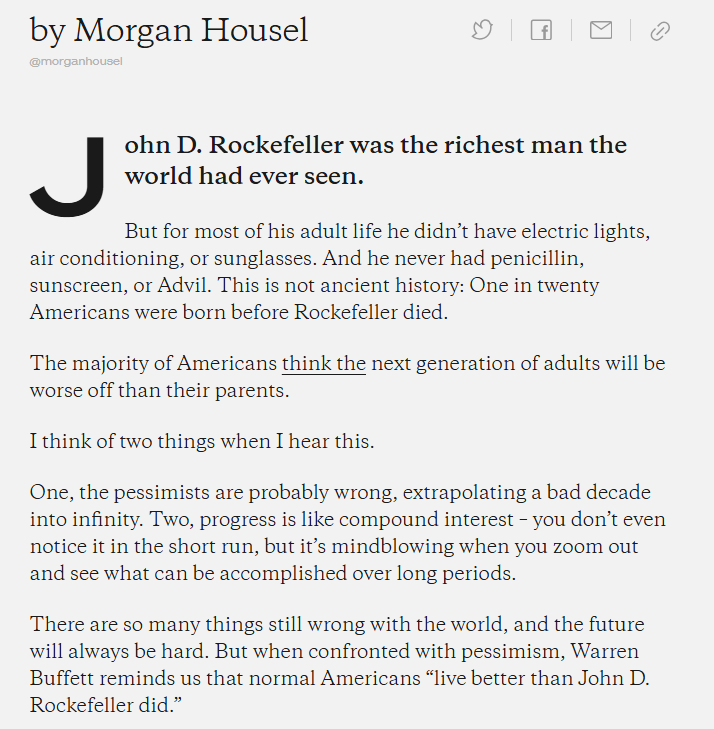

The below quote by Morgan Housel rightfully depicts this lifestyle inflation problem even though we nowadays live a richer life than John D Rockefeller.

https://collabfund.com/blog/what-a-time-to-be-alive

My thoughts drifted. The implication that his achievements were intrinsically tied to a never-ending chase for luxury struck me as hollow. Who truly benefited from his success? The rich-poor gap was broadening, social problems simmered just below the surface, and he couldn’t see it. Only focusing on the gains led to a societal fallout no one seemed willing to address, each day reinforcing a cycle of excess.

Our conversation suddenly shifted to climate change as we talk about the recent weather, a topic Mr. B approached with a dismissive wave of his hand. “Indeed, it’s a mess,” he said, “but look around you. Instead of everyone doing their part, they’re consumed by the desire to maximize wealth, to travel more, to ‘live their best lives.’” As he spoke, I couldn’t shake the feeling that he was both a participant and a critic in this spiraling world.

“Surely we need to do something,” I urged as a minimalist, hoping to stir some reflection within him. “If we all focused on reducing consumption, we’d surely help the planet.”

His laughter echoed ironically as he dismissed my concern. “As if people would prioritize that! Everyone’s concerned about their own corner of the world, not the community, let alone the planet! It’s a selfish game.”

Mr. B’s projection of individualistic success clashed with the collective consciousness I longed for. In his pursuit of wealth and status, he inadvertently illustrated a duality—the celebration of personal achievement while forsaking the greater good. Many had their sights set on extravagant dreams: lavish homes, luxury cars, Michelin style food and exclusive travel experiences. Meanwhile, Mother Earth withered under the strain of mass consumption.

In that moment, I realized the true cost of our so-called prosperity—the negligence of communal well-being and environmental health. Instead of cherishing what we had and nurturing our resources, we were merely hopping from one inflated desire to another. This wasn’t mere myopia; it was an existential threat—an unsustainable pattern that propelled us toward a dead-end.

As our meal concluded, I couldn’t ignore the irony of Mr. B’s reflections. He epitomized the challenges of a generation: individuals caught in the whirlwind of consumerism, unable to slow down or question the narrative of success. “If only people thought collectively,” I mused aloud, wondering how to inspire that shift.

“What if our life’s objective were to achieve a balanced life, rather than simply maximizing every aspect, especially on material terms?”

The above encounter reminds of the whole scene in the movie “The Big Short,” Mark Baum, portrayed by Steve Eisman, has a tense encounter with a collateralized debt obligation (CDO) manager who claims to represent the investors. Baum discovers that the manager is simply a separate entity from Merrill Lynch, casting doubt on whose interests are genuinely addressed. The manager insists he assumes no risk associated with the products, even as default rates rise during the 2008 financial crisis. Baum’s skepticism shines through as he challenges the manager’s justifications for the risky practices, emphasizing the stark contrast between Wall Street’s optimistic facade and the serious vulnerabilities in the economy.

Toward the end of their conversation, as Baum feels increasingly sickened by the CDO game, the manager condescendingly suggests that while Baum may view him as a parasite, society values his role. In a final display of arrogance, the manager seeks to compare net worth with Baum, leading Baum to dismiss him with a powerful retort, calling him an “incredibly pig piece of shit.” This confrontation underscores Baum’s critique of the financial system and its moral failings.

You can watch this scene: